A few days ago Nas kicked off an interesting discussion on Xitter about detections’ quality. I liked it, so I offered my personal insight. I then added a stupid example to illustrate my point to which DylanInfosec replied:

Would love to set some time aside and gather some OS log dumps, throw em in a SIEM and test that way or something. I guess crowd validation with a trusted diverse group could work too. Not-for-profit or anything but just to share with the community

This made me think…

I am an old-school data hoarder; as far as I remember I have always been actively looking for data of interest in a lot of places… And I must confess that the only reason I could immediately provide that stupid mimi-based regex filename search example was because I had an access to my private ‘clean’ file names dataset…

You see… over a decade ago I kicked off a personal project of mine that focused on collecting software data from CLEAN sources. While many people in the cybersecurity industry at that time primarily focused on malware collections, I decided to take a step forward and collect data that was most likely clean. So, I wrote a number of web scrapers, downloaders, used VPN and Tor where necessary and eventually built a large data set of samples that is a a collection of (most likely) clean files downloaded from publicly available sources. I didn’t stop there. I took every single sample that I downloaded and got it decompiled, whenever it was possible… then processed all the decompiled files only to build a modern, full-blown, Windows-centric clean software data collection set that I believed at that time to be far better than NIST’s.

Now, it’s been a few years and this set is getting older and older, every single day, so perhaps it’s time for it to win some brownie points in the community…

Many of our threat hunting rules depend on file names. The file I am attaching to this post includes a list of many PE file names in my collection that are known to be ‘clean’ (to be precise, these are all file names ending with the following file extensions: ‘exe’, ‘dll’, ‘drv’, ‘ocx’, ‘sys’). It goes without saying that you must treat this list as very suspicious, but I hope it will help you to write better detections…

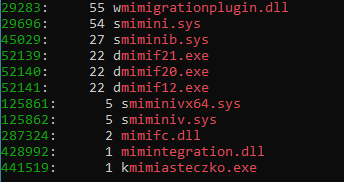

And to illustrate the point, let’s run a query that is similar to the one I did for my tweet:

rg -i "mimi.*?\.(dll|exe|sys)" _files_of_interest.su

Note: you can’t use the _files_of_interest.zip/_files_of_interest.su files for commercial purposes.