Excel is the emperor of automation. Not the SOAR type, but the local one – yours.

Why?

Its formulas and VBA capabilities can turn many awfully mundane tasks into plenty of automation opportunities…

For instance… certain programming tasks.

The case/switch syntax is a beautiful construct. It allows us to define a large set of complex if/then statements in a very elegant way. It is very often used to split a data/value set into conditions that determine the result/output/outcome based on the input.

Now, there are some programming languages that do not support case/switch statements well (not a part of its functional specification, introduced in late versions hence not fully compatible, etc.).

Writing case/switch statements for these languages is TOUGH. This is because their limitations often force us to rely on a bunch of NESTED IF clauses… Writing many of these, nested, is not for the faint-hearted. Typos, incorrect number of opening or closing parenthesis, and overall — getting lost in the complexity of this nested logic is very easy.

And this is where Excel can help a lot.

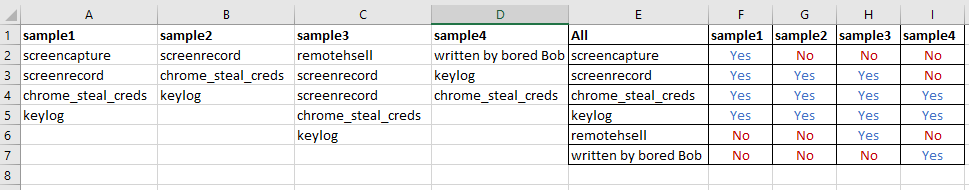

Imagine a hypothetical scenario where you have to write a code that gets this input data (names that are a loose set of Value1, Value2, Value3) to generate the output (A, B, C, D, E) based on peoples’ names:

It’s pretty straightforward in case/switch supporting programming languages to define rules based on this set, but if the only thing available are nested ifs – it’s much harder.

Let’s try though…

The first idea we can tackle is to convert these 3 values (some are empty) to an array of per-row list of values:

You will admit that the List column looks more ‘programmer friendly’ now.

The formula that produces the values in the List column is obscenely simple:

We simply build a parenthesis-embraced list of values where the first one is always present, and the two others are added only if the respective cells are not empty.

Trivial!

But how do we convert this list of values into a programmatic construct that gives us A, B, C, D or E depending on the name (one of these three values/per row)?

This is one way to do it (using ternary operator):

(if (name in ('John', 'Jack', 'Anne') ? 'A' : (if (name in ('Peter') ? 'B' : (if (name in ('Kate', 'Leo') ? 'C' : (if (name in ('Paul', 'Ariel', 'Fyodor') ? 'D' : (if (name in ('Amy', 'Maria') ? 'E' : "N/A"))))))))))

If you are curious where the formula comes from — it is from the very same spreadsheet – it is the value of the F2 cell:

And how did we build this one?

This is how:

What we do here is building a basic ternary logic where we take the one part of the comparison from the current row, and then the alternative is taken from the row below. In the end, the sort-of recursion happens and we end up with a sequence of nested ternary operators doing its work.

It may be a bit surprising, but using Excel for building complex logical statements like the one above, the one that in the end can be pasted directly to your favorite programming editor is actually very easy…

You benefit from the fact the input data is saved in Excel format and is easy to edit, plus – as long as the formulas are correct – the resulting nested constructs are written (generated) in a syntactically correct way and with far less chances to introduce a basic typo error.