In my last post I looked at ‘good’ file names. Today I will look at them again.

Sort of…

Over the years I have written a number of yara rules that use a peculiar condition that hits on an internal PE file name sometimes being preserved inside some of the PE files, both DLL and EXE… If you ever looked at an internal structure of a PE file you know that its export directory has a capability to preserve a programmer-chosen, internal file name that is compiled into the final binary file, and that internal file name often differs from the file name being used on a file system level…

Some Threat actors know about it and abuse it, but many don’t – in some cases allowing us to write very precise detection rules… That internal file name is a great forensic and telemetry artifact and it would be a crime not to use it, where applicable…

In my old Yara rules I would usually rely on this (somehow) esoteric syntax that I copied and pasted from someone else (sorry, don’t remember who that person was):

strings: $dllname = "<filename>" condition: ($dllname at pe.rva_to_offset(uint32(pe.rva_to_offset(pe.data_directories [pe.IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT].virtual_address)+12)))

which is basically a rudimentary PE file format parsing condition checking if the specific ANSI string is present at a given place inside the file’s export directory (where that internal PE file name resides) and if it matches the string I defined…

After the release of yara 4.0.0 we can use a far more simpler construct to define the very same condition – one that leverages the PE module:

pe.dll_name=="<filename>"

Now…

This internal file name preserved in the export directory of many PE files is a bit of a phenomenon because if we just focus on native Windows OS binaries we will discover a lot of interesting bits. Say, we look at the native PE files taken from the Windows 11 system32 directory — we can easily discover a number of PE files where the ‘external’ (file system-based) and ‘internal’ (PE export directory-based/pe.dll_name) file names do not match…

Here’s a quick & dirty list of such files that I’ve extracted…

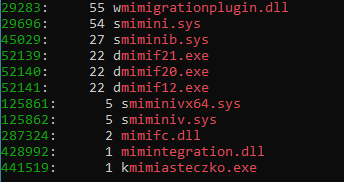

And just for a second, let me digress here – I must mention that I generated this quick&dirty file for the purpose of writing this post but then… just eyeballing its content… my attention was immediately drawn to this interesting finding…:

- The Windows’ library AppVTerminator.dll uses an internal file name of Arnold.dll. What’s more, the file exports a function called ‘IllBeBack’

If you ever watched the 80/90’s Terminator movie franchise you know this really cannot be a coincident, and a quick google session that followed led me to this gist by @mcbroom_evan. I really love to be the first reporting OS-related interesting facts, peculiarities, and things that make you go “hmmm interesting’, but I was simply late in this case! Kudos to you @mcbroom_evan!

Back to our quick & dirty list…

Looking at the internal file names used by many native Windows OS binaries we can immediately see a bit of a pattern:

- dll.dll 21

- deffile.dll 8

- stub.dll 7

- SWEEPRX.dll 3

- vm3ddevapi-release.exe 3

- vm3dum.dll 3

- vm3dum10.dll 3

- module.dll 3

- sb.dll 2

- iwb.dll 2

- USERCPL.dll 2

- smalldll.dll 2

- DeviceInfoParser.dll 2

- AppxDeploymentExtensions.dll 2

- inprocserver.dll 2

- winload.sys 2

- PACK2.dll 1

- Source.dll 1

- respub.DLL 1

- client.dll 1

Seeing these stats we can speculate that lot of early code for these native system DLLs might have been created via a simple copy&paste mechanism (dll.dll, deffile.dll, smalldll.dll and stub.dll are hardly unique file names…). Some discrepancies suggest internal struggles with terminology f.ex. PrintIsolationProxy.dll vs. PrintSandboxProxy.dll and some are completely off the limits (tcblaunch.exe/winload.exe -> winload.sys). I’d like to believe there is a logic to it, but I am not very optimistic.

Anyway…

Now that we know what this post is all about, let’s take a stab at a far larger set… that is, legitimate files produced by legitimate vendors – many of their files do include these internal PE file names too, so it would be a crime not to explore this data set…

So, here it is, a list of legitimate internal PE file names you may come across while analyzing samples. Using any of these ‘good’ internal file names as a ‘pe.dll_name==”<filename>”‘ condition in your yara rules will most likely produce FPs… You have been warned 🙂

Note: you can’t use the _file_types_PE_INTERNAL_NAME.zip/_file_types_PE_INTERNAL_NAME files for commercial purposes.